A Debit Card is a plastic card which provides an alternative payment method to cash when making purchases. Physically the card is a ISO 7810 card like a credit card, however its functionality is more similar to writing a check as the funds are withdrawn directly from the cardholder's bank account; some cards are referred to as check cards.

The customer's card is swiped through a card reader or inserted into chip reader and the merchant usually enters the amount of the transaction before the customer enters their account and PIN. There is usually a short delay while the EFTPOS (Electronic Funds Transfer at Point of Sale) terminal contacts the computer network (over a phone line or mobile connection) to verify and authorise the transaction.

In some countries the debit card is multipurpose acting as the Automatic Teller Machine card for withdrawing cash and as a check guarantee card. Merchants can also offer "cashback"/"cashout" facilities to customers, where a customer can withdraw cash along with their purchase.

The use of debit cards has become wide-spread in many countries and has overtaken the check, and in some instances cash transactions by volume. Like credit cards, debit cards are used widely for telephone and internet purchases. Anyone doubting the ubiquity of debit card usage need only witness the inconvenient delays at peak shopping times (e.g. the last shopping day before Christmas), caused when the volume of transactions overload the bank networks.

Types of debit card[]

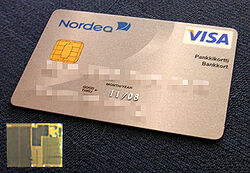

A Finnish smart card. The 3 by 5 mm security chip embedded in the card is shown enlarged in the inset. The gold contact pads on the card enables electronic access to the chip.

Although many debit cards are of the Visa or MasterCard brand, there are many other types of debit card, each accepted only within a particular country or region, for example Switch (now: Maestro) and Solo in the United Kingdom, Carte Bleue in France, Laser in Ireland, "EC electronic cash" (formerly Eurocheque) in Germany and EFTPOS cards in Australia and New Zealand. The need for cross-border compatibility and the advent of the euro recently led to many of these card networks (such as Switzerland's "EC direkt", Austria's "Bankomatkasse" and Switch in the United Kingdom) being rebranded with the internationally recognised Maestro logo, which is part of the MasterCard brand. Some debit cards are dual branded with the logo of the (former) national card as well as Maestro (e.g. EC cards in Germany, Laser cards in Ireland, Switch and Solo in the UK, Pinpas cards in the Netherlands, Bancontact cards in Belgium, etc.).

Banks in France charge annual fees for debit cards (despite card payments being very cost efficient for the banks), yet they do not charge personal customers for chequebooks or processing cheques (despite cheques being very costly for the banks). This imbalance most probably dates from the unilateral introduction in France of Chip and PIN debit cards in the early 1990s, when the cost of this technology was much higher than it is now. Credit cards of the type found in the United Kingdom and United States are unusual in France and the closest equivalent is the deferred debit card, which operates like a normal debit card, except that all purchase transactions are postponed until the end of the month, thereby giving the customer between 1 and 31 days of interest-free credit. The annual fee for a deferred debit card is around €10 more than for one with immediate debit. Most France debit cards are branded with the Carte Bleue logo, which assures acceptance throughout France. Most card holders choose to pay around €5 more in their annual fee to additionally have a Visa or a MasterCard logo on their Carte Bleue, so that the card is accepted internationally. A Carte Bleue without a Visa or a MasterCard logo is often known as a "Carte Bleue Nationale" and a Carte Bleue with a Visa or a MasterCard logo is often known as a "Carte Bleue Internationale". Many smaller merchants in France refuse to accept debit cards for transactions under €15.25 (equivalent to 100 French Francs) because of the minimum fee charged by merchants' banks per transaction. Merchants in France do not differentiate between debit and credit cards, and so both have equal acceptance. However Visa's and MasterCard's regulations prohibit merchants from setting minimum charge amounts. American Express's policy is to discourage any merchant practices that create a "barrier to acceptance" and setting minimium charge limits is such a barrier. Amex does prohibit "discrimination" against the Amex card, which means they cannot have minimum charge for Amex but not for Visa and Mastercard but they cannot have a minimum charge for Visa and MasterCard because VIsa and Mastercard prohibit this.

In the United Kingdom, banks started to issue debit cards in the late 1980s in a bid to reduce the number of cheques being used at the point of sale, which are costly for the banks to process. As in most countries, fees paid by merchants in the United Kingdom to accept credit cards are a percentage of the transaction amount, which funds card holders' interest-free credit periods as well as incentive schemes such as points, airmiles or cashback. On the contrary, debit cards do not usually have these characteristics, and so the fee for merchants to accept debit cards is a low fixed amount, regardless of transaction amount. This means it is cheaper for a merchant to accept a debit card for a large amount and to accept a credit card for a small amount. Although merchants won the right through The Credit Cards (Price Discrimination) Order 1990 to charge customers different prices according to the payment method, few merchants in the UK charge less for payment by debit card than by credit card, the most notable exceptions being budget airlines, travel agents and IKEA. Debit cards in the UK lack the advantages offered to holders of UK-issued credit cards, such as free incentives (points, airmiles, cashback etc), interest-free credit and protection against defaulting merchants under Section 75 of the Consumer Credit Act 1974. Despite these disadvantages of debit cards over credit cards, many people in the UK prefer paying with debit cards rather than credit cards, often because they fear that using credit cards will result in accumulation of unmanageable debts. Almost all establishments in the United Kingdom that accept credit cards also accept debit cards (although not always Solo and Visa Electron), but a minority of merchants, for cost reasons, accept debit cards and not credit cards (for example the Post Office).

In Germany and Belgium, many merchants, including most supermarkets, do not accept credit cards because of the higher fees charged by their banks. However, most merchants usually accept debit cards, because the fees for accepting them are much lower, for example in Germany 0.3% with a minimum of €0.08.

In Poland, local debit cards, such as PolCard, have become largely substituted with international ones, such as Visa, MasterCard, or the unembossed Visa Electron or Maestro. Most banks in Poland block Internet and MOTO transactions with unembossed cards, requiring the customer to buy an embossed card or a card for Internet/MOTO transactions only. Recently however the number of banks which do not block MOTOIO transactions on unembossed cards is increasing.

Online and offline debit cards[]

There are currently two ways that debit card transactions are processed: online debit cards and offline debit cards. Online debit cards require electronic authorization of every transaction and the debits are reflected in the user’s account immediately. The transaction may be additionally secured with the personal identification number (PIN) authentication system and some online cards require such authentication for every transaction, essentially becoming enhanced automatic teller machine (ATM) cards. One difficulty in using online debit cards is the necessity of an electronic authorization device at the point of sale (POS) and sometimes also a separate keypad to enter the PIN, although this is becoming commonplace for all card transactions in many countries. Overall, the online debit card is generally viewed as superior to the offline debit card because of its more secure authentication system and live status, which alleviates problems with processing lag on transactions that may have been forgotten or not authorized by the owner of the card. Banks in some countries, such as Canada and Brazil, only issue online debit cards.

Offline debit cards have the logos of major credit cards (e.g. Visa or MasterCard) or major debit cards (e.g. Maestro) and are used at point of sale like a credit card. This type of debit card may be subject to a daily limit, as well as a maximum limit equal to the amount currently deposited in the current/checking account from which it draws funds. Offline debit cards in some countries are not compatible with the PIN system, in which case they can be used with a forged signature, since users are rarely required to present identification. Transactions conducted with offline debit cards usually require 2-3 days to be reflected on users’ account balances. This type of debit card is similar to a secured credit card.

Many debit cards are actually capable of accomplishing both types of transactions, depending on the availability of proper equipment at the POS.

In the United Kingdom, Solo and Visa Electron are examples of online debit cards, which are typically issued by banks to customers whom the bank does not want to go overdrawn under any circumstances, for example under-18s.

"Credit" and "debit" purchases[]

Typical debit card transaction machine, branded to McDonalds.

In some countries (e.g. the United States and Australia), terminals allow the user of a Visa or MasterCard debit card to choose whether the purchase is a "credit" or "debit" purchase. In a "credit" purchase, the user signs a charge slip like in a traditional credit card purchase; in a "debit" purchase, the user enters a PIN. In either case, the user's bank account is debited. Some merchants in the United States have recently been allowed to bypass the signature requirement for a credit sale if the total sale is under a certain dollar amount. This is based on the assumption that customers want a fast and simple point-of-sale process, and low-value transactions are not the activity of a fraudulent user.

One problem surrounding the use of bank account based debit cards is their use at a self-service gas pump like those common in the United States. The customer might want to purchase fuel on their debit card, but the pump's computer does not know how much fuel the customer wants. The pump is activated by the customer presenting their card to a card reader (see methods described above) and possibly entering a PIN. At this point the pump will dispense fuel, though no sales transaction has completed. The pump has no way of knowing how much fuel will be sold, or more importantly, how much money is available in the customer’s debit account. In a typical sale transaction, trying to spend more money than is available in your account (credit or debit) will result in a "no-sale" alert to the merchant, and the sale does not occur. At a self-serve fuel pump, the fuel is already in the customer's tank by the time the bank knows the final sale price. Several solutions to this problem are in place, but the concept of delivering the merchandise before the sales transaction plagues the debit card system.

In some countries and with some merchant service organisations (as of this writing), a "credit" transaction is without cost to the purchaser beyond the face value of the transaction, while a small fee may be charged for "debit" transactions (although it is often absorbed by the retailer.) Other differences are that "debit" purchasers may opt to withdraw cash in addition to the amount of the debit purchase (if the merchant supports that functionality); also, from the merchant's standpoint, the merchant pays lower fees on a "debit" transaction as compared to "credit" transactions.

The fees charged to merchants on "credit" debit card purchases -- and the lack of fees charged merchants for processing "debit" debit card purchases and paper checks -- have prompted some major merchants to file lawsuits against debit-card transaction processors such as Visa and MasterCard. Visa and MasterCard recently agreed to settle the largest of these lawsuits and agreed to settlements of billions of dollars.

Many consumers prefer "credit" transactions because of the lack of a fee charged to the consumer/purchaser -- and many terminals at PIN-accepting merchant locations now make the "credit" function more difficult to access. Also, in the case of a benign or malicious error by the merchant and/or bank, a debit transaction may cause more serious problems (e.g. money not accessible; overdrawn account) than in the case of a credit or charge card transaction (e.g. credit not accessible; over credit limit).

To the consumer, a debit transaction is perceived as occurring in real-time; i.e. the money is withdrawn from their account immediately following the authorization request from the merchant, which in some countries, is the case when making a PIN-based purchase. However, when a purchase is made using the "credit" option, the transaction places an authorization hold on the customer's account which then may take several days to be reconciled and hard-posted to the customer's account. This is in contrast to a typical credit card or charge card transaction which can have a lag time of a few days before the transaction is posted to the account, and many days to a month or more before the consumer makes repayment with actual money.

The two types of transactions are actually online ("Debit") and offline ("Credit") as described in the previous paragraph.

Chip and PIN[]

In many countries, the use of PIN validated transactions with smartcard chip readers is being strongly encouraged by the banks as a method of reducing cloned-card fraud; to the extent that cardholder-present transactions will soon not be possible in these countries without knowledge of a PIN, and the POS terminal reading the smart card chip on the card.

Cards for mail, telephone and Internet use only[]

Special pre-paid Visa cards for mail, telephone (MOTO) and Internet use only are made available by a small number of banks. They are sometimes called "virtual Visa cards", although they usually do exist in the form of plastic. Such cards can be used whenever the remote store accepts Visa cards. Before making the transaction, the customer transfers the required amount of money from his main account to the card's sub-account using the bank's website or the telephone. Next, the customer gives the card number and the CVV2 code to the merchant, who authorizes the transaction electronically, as with a regular Visa card. If there is enough money on the sub-account, the bank grants the authorization and locks the adequate amount on the sub-account.

Such a card prevents fraud by a card number thief even if the card is not blocked, because the customer normally does not store any money on the sub-account and fraudulent transactions do not get authorized by the bank. For extra security, the CVV2 code is not printed on the card but rather sent separately to the customer in a secured envelope.

The bank also rejects local transactions, that is ones that are not made over the Internet, mail or telephone. However, some merchants use software incompatible with Visa regulations and send authorization requests that wrongly tell the bank that the transaction is not a MOTO/Internet one, in which case the bank rejects the request. Additionally, some merchants do not use electronic authorization at all, in which case the transaction cannot be completed as well. For these two reasons the card is unusable with a small minority of Internet, telephone and postal stores.

Financial access[]

Debit cards and secured credit cards are popular among college students who have not yet established a credit history, or the "unbanked". Debit cards may also be used by expatriated workers to send money home to their "unbanked" families holding an affiliated debit card.

Debit cards around the world[]

In some countries, banks tend to levy a small fee for each debit card transaction. In some countries (e.g. the UK) the merchants bear all the costs and customers are not charged. There are many people who routinely use debit cards for all transactions, no matter how small. Some (small) retailers refuse to accept debit cards for small transactions, where paying the transaction fee would absorb the profit margin on the sale, making the transaction uneconomic for the retailer.

Canada[]

Canada has a nation-wide EFTPOS system, called Interac Direct Payment. Since being introduced in 1984, IDP has become the most popular payment method in the country, surpassing even regular cash payments in 2001.

In Canada, the debit card is sometimes referred to as a "bank card". It is simply a bank client card, issued by a bank, providing client access to funds and other bank account transactions, such as transferring funds, checking balances, paying bills, etc, as well as point of purchase transactions connected on the Interac network. Since its national launch in 1994, Interac Direct Payment has become so widespread that, as of 2001, more transactions in Canada were completed using debit cards than cash. This popularity may be partially attributable to two main factors: the convenience and safety of not having to carry cash (or at least, large amounts of cash) and the prevalence and availability of "bank machines" (automated teller machine or "ATM", or automated bank machine or "ABM") on the network. However, Canadians tend to use Interac more often than ABMs. Almost every merchant, restaurant, gas station, or service provider is equipped with Interac technology. Interac is a small hand held device located at the cash of every business. The customer swipes his card, enters his PIN, and accepts the purchase. The charges are immediately withdrawn from the customer's account.

Debit cards may be considered similar to stored-value cards in that they represent a finite amount of money owed by the card issuer to the holder. They are different in that stored-value cards are generally anonymous and are only usable at the issuer, while debit cards are generally associated with an individual's bank account and can be used anywhere on the Interac network. Debit cards usually offer some protection against loss, theft, or unauthorized use while stored-value cards usually do not.

In Canada, the bank cards can only be used at POS and ATM's. There used to be no Visa or Mastercard branded debit cards in Canada.

UK[]

In the UK debit cards (an integrated EFTPOS system) are an established part of the retail market. The term EFTPOS is not used at all by the public, debit card is the generic term used. Cards commonly in circulation include Maestro (previously Switch), Solo, Visa Debit (previously Visa Delta) and Visa Electron. Banks do not charge customers for EFTPOS transactions in the UK, but some retailers make small charges, particularly where the transaction amount in question is small. The UK is in the process of converting all debit cards in circulation to Chip and PIN, based on the EMV standard, to increase transaction security.

New Zealand[]

The EFTPOS system is highly popular in New Zealand, with more EFTPOS terminals per head of population than any other country[1], and being used for about 60% of all retail transactions[2]. According to the largest EFTPOS network provider, "New Zealanders use EFTPOS twice as much as any other country."[3]

Virtually all retail outlets have EFTPOS terminals, particularly supermarkets, dairies, service stations, and bars. Increasingly Taxi operators and even businesses operating from stands at events have mobile EFTPOS terminals.

New Zealanders use EFTPOS for both small and large transactions. It would not be unusual for a New Zealander to use an EFTPOS card to pay for an amount as small as $1 NZD. Because EFTPOS is such an integral part of spending in New Zealand, rare network failures cause tremendous delays, inconvenience and lost income to businesses who must resort to swipe machines to process EFTPOS transactions until the network returns to service.[4] Typically New Zealand merchants do not pay per transaction like in Australia and other countries. The transaction fees are typically borne by the customer, and retailers pay a fixed monthly equipment rental fee. As bank accounts for students, under 18 year old and elderly do not attract many (sometimes none at all) electronic transaction fees, the use of EFTPOS by the younger generations is becoming highly prevalent. In recent times, major banks have started to offer accounts with no EFTPOS transaction fees.

The Bank of New Zealand introduced EFTPOS to New Zealand in 1985 through a pilot scheme with petrol stations.

EFTPOS is operated through two primary networks. One, EFTPOS NZ, owned by ANZ National Bank, and a second operated by Electronic Transaction Services Limited which is owned by ASB Bank, Westpac, ANZ National Bank and the Bank of New Zealand. The ETSL network processes approximately 80% of all EFTPOS transactions in New Zealand on their Paymark EFTPOS network and has over 60,000 points of sale.[5]

During July 2006 the five billionth EFTPOS payment flowed across the ETSL/Paymark EFTPOS network since the electronic form of payment was introduced in New Zealand in 1989.[6]

Australia[]

EFTPOS is very popular in Australia and has been operating there since the 1980s. EFTPOS-enabled cards are accepted at almost all swipe terminals able to accept credit cards, regardless of the bank that issued the card, including Maestro cards issued by foreign banks, with most businesses accepting them, with 450,000 Point Of Sale terminals[7]. EFTPOS cards can also be used to deposit and withdraw cash over the counter at Australia Post outlets participating in giroPost, just as if the transaction was conducted at a bank branch, even if the bank branch is closed. Electronic transactions in Australia are generally processed via the Telstra Argent network - which has recently superseded the old Transcend network in the last few years. Both were provided by Telstra, Australia's incumbent telco.

Australia operates both electronic credit card transaction authorization and traditional EFTPOS debit card authorization systems. The difference between the two being that EFTPOS transactions are authorized by a personal identification number (PIN) while credit card transactions are usually authorized by the printing and signing of a receipt.

Generally credit card transaction costs are borne by the merchant with no fee applied to the end user while EFTPOS transactions cost the consumer an applicable withdrawal fee charged by their bank.

The introduction of Visa and Mastercard debit cards along with regulation in the settlement fees charged by the operators of both EFTPOS and credit cards by the Reserve Bank has seen a continuation in the increasing ubiquity of credit card use among Australians and a general decline in the profile of EFTPOS. However, the regulation of settlement fees also removed the ability of banks, who typically provide merchant services to retailers on behalf of Visa, Mastercard or Bankcard, from stopping those retailers charging extra fees to take payment by credit card instead of cash or EFTPOS. Though only a few operators with strong market power have done so, the passing on of fees charged for credit card transactions may result in an increased use of EFTPOS.

Germany[]

Over recent years, in Germany debit cards have gained tremendously in acceptance. Facilities already existed before EFTPOS became popular with the Eurocheque card, an authorization system initially developed for paper cheques where in addition to signing the actual cheque, customers were issued a card that needed to be shown along side the cheque as security measure. Those cards could and can also be used on ATM Terminals and at EFTPOS, which is nowadays their only function, since the Eurocheque system (along with the name, but they're still referred to as Eurocheque cards by most people) was abandoned in 2002 during the transition from Deutsche Mark to the Euro. In 2005, most stores and petrol outlets have EFTPOS facilities. Processing fees are deducted from businesses, and because of this, some business owners refuse debit card sales for totals below a certain amount, usually 5 or 10 Euros.

Around 2000, an alternative method for EFTPOS payment was introduced, dubbed "Geldkarte" ("money card"). It uses a smart card chip on the front of a standard issue Eurocheque card (which still had the magnetic stripe on the back). This chip can be loaded with up to 200 Euros, and is advertised as means for medium to very small payments, down to the low euro or even cent range, as no processing fees are deducted by banks. It has not gained the popularity its inventors have hoped for, however this could change when this chip will be used as means of age verification at cigarette vending machines, which will become mandatory in 2007.

Chile[]

Chile has an EFTPOS system called Redcompra (Purchase Network) which is currently used in at least 23,000 establishments throughout the country. Goods may be purchased using this system at most supermarkets, retail stores, pubs and restaurants in major urban centers.

The Netherlands[]

In the Netherlands using EFTPOS is known as pinnen (pinning), a term derived from the use of a Personal Identification Number. PINs are also used for ATM transactions, and the term is used interchangeably by many people, although it was introduced as a marketing brand for EFTPOS. The system was launched in 1987, and currently has 166,375 terminals throughout the country, including mobile terminals used by delivery services and on markets. All banks offer a debit card suitable for EFTPOS with current accounts.

PIN transactions are usually free to the customer, but the retailer is charged per-transaction and monthly fees. Equens, an association with all major banks as its members, runs the system, and until August 2005 also charged for it. Responding to allegations of monopoly abuse, it has handed over contractual responsibilities to its member banks, who now offer competing contracts. Interpay, a legal predecessor of Equens, was fined EUR 47 million in 2004, but the fine was later dropped, and a related fine for banks was lowered from EUR 17 to EUR 14 million. Per-transaction fees are between 5-10 eurocents, depending on volume.

Credit cards use in the Netherlands is very low, and most credit cards cannot be used with EFTPOS, or charge very high fees to the customer. Furthermore, debit cards can be used in the entire EU for EFTPOS, and most debit cards are Cirrus cards.

United States[]

In the US, EFTPOS is usually referred to simply as POS or Point-of-Sale by the financial industry and merchants. The same interbank networks that operate the ATM network also operate the POS network. Most interbank networks, such as Pulse, NYCE, MAC, Tyme, SHAZAM, STAR, etc. are regional and do not overlap, however, most ATM/POS networks have agreements to accept each other's cards. This means that cards issued by one network will typically work anywhere they accept ATM/POS cards for payment. For example, a NYCE card will work at a Pulse POS terminal or ATM, and vice versa.

Japan[]

In Japan people usually use their Template:Nihongo, originally intended only for use with cash machines, as debit cards. The debit functionality of these cards is usually referred to as Template:Nihongo, and only cash cards from certain banks can be used. A cash card has the same size as a VISA/MasterCard. As identification, the user will have to enter his or her four-digit PIN code when paying. Unlike other debit card services, J-Debit is only available during certain times of the day.

As an alternative to J-Debit, the Japanese post office started offering what they call "Japan's first VISA debit card" in mid-2006.

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |

|